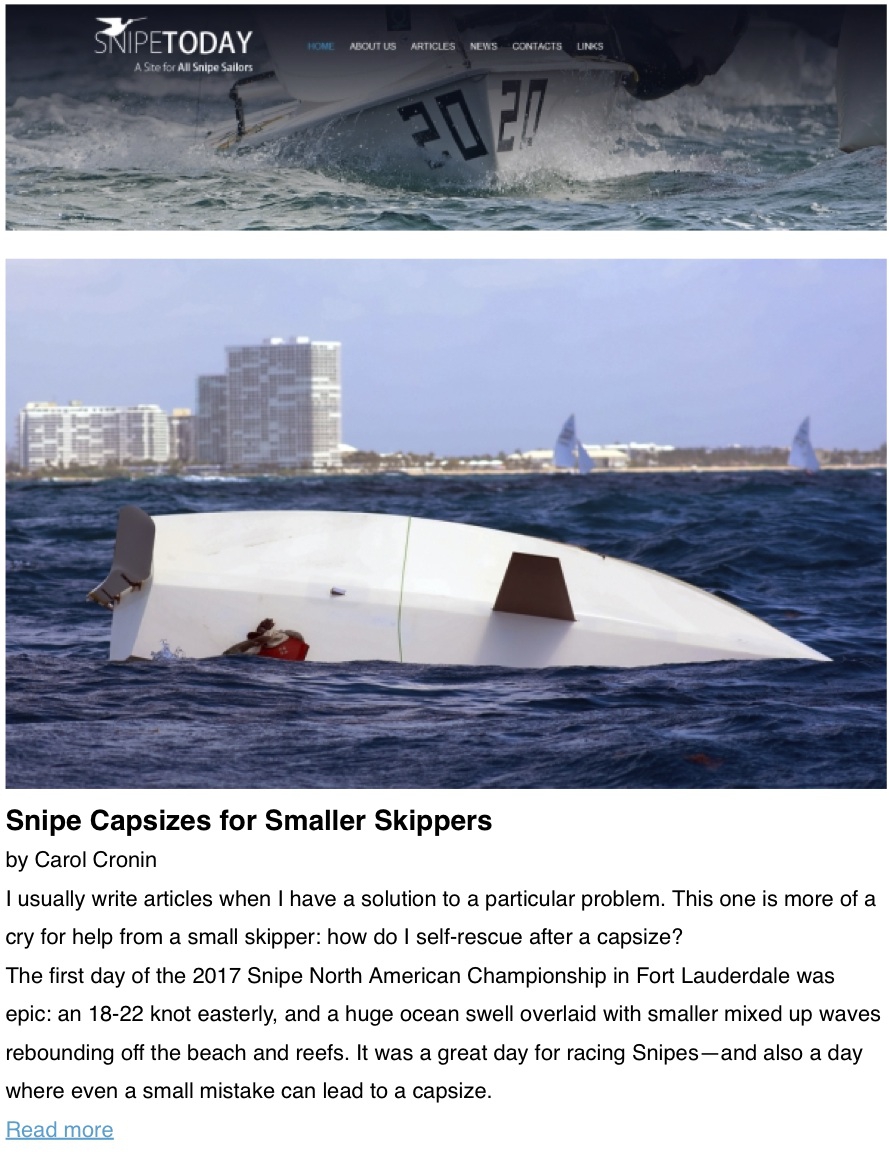

Snipe Capsizes for Smaller Skippers

I usually write articles when I have a solution to a particular problem. This one is more of a cry for help from a small skipper: how do I self-rescue after a capsize? The first day of the 2017 Snipe North American Championship in Fort Lauderdale was epic: an 18-22 knot easterly, and a huge ocean swell overlaid with smaller mixed up waves rebounding off the beach and reefs. It was a great day for racing Snipes—and also a day where even a small mistake can lead to a capsize. ...

I usually write articles when I have a solution to a particular problem. This one is more of a cry for help from a small skipper: how do I self-rescue after a capsize?

The first day of the 2017 Snipe North American Championship in Fort Lauderdale was epic: an 18-22 knot easterly, and a huge ocean swell overlaid with smaller mixed up waves rebounding off the beach and reefs. It was a great day for racing Snipes—and also a day where even a small mistake can lead to a capsize.

…

I started sailing Snipes in 1990 as a crew, and over the next decade I learned a lot from a long list of skippers—including how to recover from flipping. As a former member of the crew union, I still remember the basic steps for a forward teammate: don’t get trapped under or separated from the boat; help your skipper right the boat; and once you are both safely back onboard, be prepared to act as a psychologist. (You may also have to defend yourself when blamed for the capsize, even though it was probably not your fault.)

When I first moved to the back of the boat, I learned a lot by chatting with other skippers after sailing. (That’s still true, actually.) At one particular party, I looked over at Kim to find her pointing at our group and laughing. When I asked her later what was so funny, she said, “You’re a foot shorter than the rest of them!”

While we’ve gradually improved our tuning and boathandling to compensate for my smaller stature, it wasn’t until my very first capsize as a skipper that I thought about how much size matters there too. So in an attempt to share knowledge and perhaps spark some solutions, here’s what happened.

In the first race of the North Americans, Linda and I rounded the weather mark in about eighth place and jumped up onto a plane. The mark was low, so we launched the pole and were just settling in for a fun ride when a wave simultaneously pushed the boat to leeward and washed me out of the boat to windward. I managed to hold onto the mainsheet, but all I could do was watch as the boat pirouetted into a death-roll-capsize. Linda ended up pinned under the main but managed to swim herself clear—and fortunately our closest competitor was able to head up (poled-out jib luffing furiously) enough to avoid running us over.

The boat was on its side, so I grabbed the centerboard and placed my feet on the rail that was underwater. Usually the next step is to pull the centerboard up all the way for more leverage, but due to a tight trunk, my short stature, and less upper body strength than I used to have, I wasn’t able to move it more than a few inches. The boat slowly turtled and also pivoted around until the mast was facing upwind, so we hung on patiently until the right wave/wind combination picked up the tip of the mast and blew the boat over to leeward again. (And according to the top photo, the board went all the way down on its way through.)

By the time I swam around to the other side again, the boat had already turtled again. And that’s when I realized that I could not reach the centerboard. The Perssons float higher than Jibetechs, so I like to think that in my own boat I’d be able to self-rescue (though I’m not very eager to test this theory). In this particular boat, the board was well beyond my reach.

Fortunately, there was a safety boat standing by and as soon as we asked for help, they came over. Brian Buckley jumped in the water, dove under the boat to release the pole launcher line, and then bench-pressed himself up onto the side rail until he could grab the centerboard. Less than a minute later the boat was upright, and he was pulling me back aboard.

(A side note: even if I’d managed to right the boat, I’m not sure I could’ve heeled it over enough to get aboard by myself.)

While the boat was upside down, the rudder had popped off—in spite of a very stiff and secure rudder lock. (As a result, I highly recommend tying in your rudder; see a photo below of the shockcord arrangement I use on my own boat.) The safety boat retrieved the rudder, and I was able to get it onto the gudgeons thanks to Brian swimming the bow into the wind. Since the boat was rolling around in big waves, I doubt it would’ve been possible to get the rudder installed again without that assistance.

Next I pulled Linda back into the boat, and then we began to retrieve our various water bottles and assess any damage. (Thankfully, we were both fine and so was the boat.) Then we ambled back down to the starting area to wait for the next race.

In spite of starting off the regatta with a DNF, we eventually finished seventh overall. But ever since that first race, I’ve thought long and hard about how we could’ve managed to self-rescue—and I haven’t come up with any answers. While the big waves made everything harder, even in flat water I couldn’t have reached the centerboard on a boat that floats so high. Grabbing the rudder doesn’t help (even if it had been tied on), because there are no rails on the transom to stand on and nothing but a sharp dangerous bailer within reach.

The reason I know how dangerous that bailer can be is because Charlie Bustamante cut his fingers on it during a similar capsize at the 2017 DonQ. The irony in all this is that a week before my own capsize, I had just edited their story … which is why I already knew to avoid any interaction with the bailer.

Those of you who are a more typical “skipper-size” (and those with more upper body strength) may not ever need to think about this… but if anyone has ideas for how I could possibly self-rescue after the next capsize, please send them to [email protected]. Meanwhile, thanks to Lauderdale Yacht Club for the well-trained safety boat, and special thanks to Brian Buckley; Brian, when you’re old enough, I’ll buy you a beer.

(Photo credits: cover photo by Lauderdale Yacht Club; photos 1-5 by Matias Capizzano; 6-7 by Marco Midolo)

Leave a reply

Your email address will not be published. Your comment will be revised by the site if needed.

0 comments